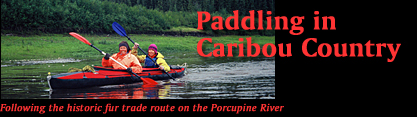

Paddling in Caribou Country:

Following the historic fur trade route on the Porcupine River

(Part II)

|

After 10 days in the wilderness, we arrive in Old Crow.

Tired, because we had to battle against a fierce headwind all

afternoon, we carry our boats and gear up the steep embankment to a

grassy area in front of the Anglican Church, where some tents billow

in the wind. We are curious about our fellow campers, but no one is

home at first, so we set up camp and cook some dinner. The news of our

arrival has already spread through town and the locals come by to

chat, or pass in their ATVs, smiling and waving. One of the first

questions we are asked is: “Have you seen any caribou?” |

|

Lunch spot upstream from Old Crow.

|

We walk the dirt roads through town. There is a

Northern Store, a community hall, an RCMP post, and a Nursing Station. One

front yard has a display of caribou antlers in various sizes, and on a

street corner is a sign post decorated with antlers. From a public phone

outside the RCMP post I make a phone call home. I am glad we have made it

here, but I am still concerned about my cough. I hope it’s nothing

serious; otherwise it could jeopardize my continuation of the trip.

|

Kurt and Teja at the campsite

in Old Crow, shortly after our arrival.

|

Karin and Kurt with Irwin,

who graciously offered us his house.

|

Front yard in Old Crow.

|

Back at the campground, we meet our fellow campers,

a group of students from Appalachian State University. They are on a field

trip to gather information about the issue surrounding the proposed oil

exploration in the ANWR, and the impact this would have on the caribou and

on the indigenous people. After living in the wilderness, it feels strange

to be camping in such a public spot, with people visiting late into the

northern night. Also, there is no public washroom, but luckily someone

directs us to an outhouse behind the pastor’s house. The wind stops suddenly in the morning. Then the

rain starts. Soon, puddles are forming around our tents. This is no

weather for paddling, so we stay put. As we huddle in our tents, there is

a knock on the tent fly and a voice inquires “are there kids inside here?

Those kids should not be out in the rain. Come to my house!” This is how

we meet Irwin, an older member of the community. He offers us his home,

while he moves in with his brother.

Irwin’s home is rustic and untidy, but we are

grateful to have been offered a warm, dry place with a roof. In the dark

hallway are several freezers, and some buckets with fish. The living

room/kitchen has a wood stove and a large TV, which Irwin encourages us to

use. We are more interested in the bathtub and shower. A small bedroom

completes the layout. Pictures of family members and small children (his

grandchildren?), and a framed photo of a guy in uniform adorn the walls.

Several dogs are tied up in the backyard. Teja and Tarim make faces

through the glass of the backdoor, and the dogs get all excited. The rain

continues the whole day. We stay in the house most of the day and only

venture out to go to the Northern Store, where I buy a pair of rubber

boots.

In the evening, Irwin brings a plate with a roast

duck, green beans and noodles. “This is for the kids,” he says and puts it

on the kitchen table. Teja and Tarim finish it off in no time. How I

coveted that duck! But dinner for us adults is noodles and a watery tomato

sauce. Before going to bed, we visit the students in the church, where the

pastor invited them to spend the night. Sitting in the pews and listening

to the crackling fire in the wood stove, we talk about the history of the

area.

|

For thousands of years, the site of Old Crow

had been a gathering place for families going down the Porcupine River

(called Ts'it Han in Gwitchin*) to trade. In the 1940's the Anglican Mission moved from

Rampart House, at the Alaskan border, to Old Crow where a store had

opened. A public school was built, and the community became a

year-round settlement. Today, with a population of about 300, Old

Crow is the only permanent settlement on the Porcupine River in

Canada. Old Crow and the river are named after the Old Crow Hills,

which lie behind the village. The name “Old Crow” is derived from a

former chief, whose name meant "Crow-May-I-Walk", which was rendered

into “Old Crow” by the first white men in the area. |

I spend part of the night sitting up and coughing.

This is the low point for me on the trip. I am tired of being damp and

cold, and of the sleepless nights I’ve been having. Should I continue? If

not, how could Karin paddle the boat all by herself? Or, if I flew south

with the boat, how could the four of them complete the trip in one kayak?

In the morning, I visit the Nursing Station to have

my lungs checked. The friendly nurse assures me I don’t have bronchitis or

a lung infection. Armed with a bottle of cough syrup, I walk towards the

river. The rain has stopped. Kurt and Karin have already packed up our

gear and got the boats ready. I am grateful because I don’t feel energetic

enough to carry the boat down to the river. As a farewell gift, Irwin

gives us a fish. Again, we are touched by his kindness.

|

By 10 am we’re setting off into the mist. Within

a few hours, we stop to build a fire to warm ourselves. Kurt is upset

because he can’t find his camera. He suspects he’s left it on the

shore in Old Crow. I reassure him that if someone from the community

has found it, he’ll get it back some day. As we continue downstream,

the mist turns to rain. We’re fed up with all this rain so when we

spot a cabin on the river bank, we decide to call it a day and stay in

the cabin. The door, fastened with some string, is easy to open. There

is a bed, covered with a caribou hide, a Yukon stove, a small table,

and five chairs. We build a fire and cook the fish. In the morning, we

leave a thank-you note on the table. |

|

Shelter from the rain: a hunters cabin.

|

We have now reached the Ramparts, a 50 km stretch near the

Yukon/Alaska border, with nearly continuous cliffs that rise between

250 and 500 feet above the river. Just as we enter the canyon, the

headwind picks up. Fast water in constricted canyons, and frequent

strong wind gusts, force us to stay alert, even after seven hours of

paddling, with aching shoulders and backs. But it is exhilarating,

too, to ride the wind-swept, brown river, each turn revealing a new

view of the purple and brown cliffs. Around 6:30 pm we finally reach

Rampart House, the former HBC post, situated high above the river, at

the Canada/Alaska border. Upon landing, we notice a flat-bottomed boat

with outboard engine on the shore and hear the sound of a chain saw.

We meet Leonard, a friendly Gwitchin, who shows us the restoration

work he’s been doing on the buildings. He’s been on his own here for

several days, but the rest of the crew is expected to arrive this

evening from Old Crow.

|

At the entrance to the Ramparts, we encounter a

strong headwind.

|

Rampart House: site of the former HBC post at

the Canada/USA border.

|

Remnants of St. Luke's Church at Rampart House.

|

I wander among the remnants of log houses. Weathered

boards, sunken floors, broken roof trusses, supported by gleaming new

wood. Behind the buildings, a field of tall fireweed, the blossoms faded.

A Canadian flag flaps in the breeze.

|

In 1842, John Bell of the HBC became the first

white man to travel down the Porcupine River, discovering what the

indigenous people had known all along – that the Porcupine River

provided a natural trade route into the Yukon River Valley. In 1845

the HBC established a trading post at the confluence of the Yukon

and Porcupine Rivers (Fort Yukon). When the United States purchased

Alaska in 1867, the HBC was forced to leave Alaska. The company then

moved its post upstream on the Porcupine River to Rampart House [Old

Rampart] where it remained until 1890, when a more accurate survey

showed that it was still slightly west of the 141st meridian. Again,

the post was moved, this time to Rampart House within the Canadian

border. From early 1900 until the 1920s, a church, a Northwest

Mounted Police post, and a store were located here. By the 1940's

the Anglican Mission had moved to Old Crow where a store had opened

and a new settlement was established. By 1947 the last resident had

left

Rampart House. |

We sit on camp chairs under a blue tarp, and Leonard

offers us tea. A hunk of caribou meat is hanging above the fire. A brief

rain shower descends. “So much rain this summer,” says one of the crew

members. They ask whether we have seen caribou. Since the Driftwood River,

we haven’t seen any. Then we return to our campsite – a cleared ledge

above the river, a short walk from the buildings. Cooking dinner, I stay

close to the fire to avoid the mosquitoes and noseeums.

We are invited for breakfast at the work camp.

Sitting on benches in the cozy wall tent, we feast on pancakes,

sausages, scrambled eggs, oranges and bananas, and talk to the staff about

the river, about their work, and about the

history of this place.

With a fast current, we continue downstream, through the Upper Ramparts.

At the site of Old Rampart, we first

investigate the Salmon Trout River, a small stream, surrounded by rock

walls and dark spruce forest. But the only

gravel bar we see is too small for a campsite, so we head back out, land

in a tiny eddy, and walk up to the site

where Old Rampart used to be. There are only a few tumble-down log cabins,

the fireweed and raspberry bushes

are nearly chest-high, and the mosquitoes are having a hey day. Not a good

place to camp. Further downstream, we

find a large gravel bar, and decide to camp there for the night. After a

pleasant evening, I go to bed and sleep all

night without coughing. Kurt and Karin unsuccessfully try to wake me

during the night when they spot a black bear

across the river (I’m the only one who has brought bear spray.)

|

Paddling through the Upper Ramparts

of the

Porcupine River.

|

In the Lower Ramparts.

|

Old cabin at the abandoned settlement

of

Henderson's Village. |

The next day, past Canyon Village, an abandoned native settlement, we meet

up with two power boats, carrying the

students downstream, towards Fort Yukon. It’s nice to see them again, and

they deliver Kurt’s camera! The pastor

had found it on the beach. Kurt is happy. The students also tell us that a

small party with inflatable canoes is ahead

of us, paddling from Old Crow to Fort Yukon, and that three German

students have arrived in Old Crow.

They had

built a log raft, launched it into the Eagle River near the Dempster

Highway, and floated down the Porcupine. But

their progress has been very slow, so we don’t expect to run into them

during the remainder of our trip. They had

built a log raft, launched it into the Eagle River near the Dempster

Highway, and floated down the Porcupine. But

their progress has been very slow, so we don’t expect to run into them

during the remainder of our trip.

Now that we are in Alaska, the weather seems to have improved. On sunny

days, when the paddling is easy, we can

hear Kurt ahead of us, impersonating Romans and Gauls as he spends hours

reading to the kids from one of the two

Asterix books they have brought on the trip.

Now that we’re more than half-way through the journey, the days seem to

pass faster. But the daylight is slowly decreasing. I notice it because

once, at the confluence of the Colleen River, we wake up around 1 am and

notice that the water is encroaching on our tents. So we pack up and move

the tents to the highest possible spot. To locate all my belongings in the

dark, I need to use my head lamp for the first time.

Shortly before reaching the Colleen River, we spot a

boat on the shore and hear a chain saw. As we paddle by, a man emerges

from the bush. “Hello, come and stop for a chat!” he calls. We meet Joe, a

paramedic from Fairbanks,

who has been here all by himself for several weeks, building a log cabin.

To keep the bears out, he has built a solar-powered electric fence around

his site. He tells us that his wife is planning to fly in next week,

intending to land on the gravel bar at the mouth of the Colleen River –

our campsite for the night. The next morning, as we are ready to leave, he

pays us a visit in his boat. He realizes that there is no more landing

spot for a plane, since most of the gravel bar is under water.

The Porcupine River now moves through the Lower

Ramparts, another stretch of cliffs, passing John Herberts village, an

abandoned settlement, and then enters the Yukon Flats, a vast area of

low-lying bush, swamps and oxbow lakes. Here, the river splits into many

channels and we have to navigate carefully not to get stuck in a dead end

channel. Fortunately, we have good maps, and Kurt is an excellent

navigator. We take several short cuts through side channels, called

sloughs, to detour around the heavily meandering main channel.

Henderson Slough: steep mud banks, topped with black

spruce. Snags along the shoreline. Dark water, still flowing with a swift

current.

Returning into the main channel, we get hit by the

headwind. Karin and I are paddling hard to keep up with Kurt, who doesn’t

seem to be fazed by the wind at all. Then we enter Six Mile Slough, a

smaller side channel, where the strength of the headwind is diminished.

After two hours of paddling, we take a break, and then return to the main

channel. Strong gusts hit us. We can barely make head way and the few

kilometres to the entrance to Nine Mile Slough seem a long way. When we

finally reach Nine Mile Slough, we see Kurt waiting for us, close to

shore. Suddenly Karin says, “There’s a bear.” The dark-brown bruin is

ambling along the shore, less than 50 metres from Kurt’s boat, heading

towards him. Then it stops, and, upon becoming aware of us, powers up the

steep embankment and disappears in the bush. Tarim and Teja, who’d never

seen a grizzly before, find the bear’s movement funny. “We saw a grizzly

with a wobbly bum,” they would later recall the incidence.

|

The grizzly powers up the embankment after becoming

aware of us.

|

High winds, dark clouds, and warm sun at Nine Mile

Slough camp.

|

Peaceful evening at Nine Mile Slough camp after the

wind has died down.

|

Shortly after the bear sighting, Karin and I run

aground on a sand bar. I have to get out to pull the boat into deeper

water. Luckily, we’re sitting on smooth sand, so there’s no danger to the

hull. By the time we meet up with Kurt again, we are tired, and ask him to

tow us for a while. He wants to complete Nine Mile Slough and make it back

to the main river the same day. Handing him the bow line, we sit back and

relax, while the shoreline passes by. The joy ride doesn’t last long.

Around the bend, we can see the main river, and the headwind is back! Kurt

wants to cross the river, with us in tow, to a large gravel bar, where he

intends to camp. Noticing the waves, we doubt that he can tow us across,

so we grip our paddles and dig in. Now we really get a feeling of the

river’s strength! Brown waves pile up beside us, spray hits our faces. For

a moment, the current seems to stall our progress. Then, another gust

hits. I stab at the waves. Paddle, paddle! I focus on the shore ahead.

Will we make it? The gravel bar in front of us is sliding past at a rapid

pace. Then we hit an eddy, turn the bow into the current, and reach

shallow water. Made it! But the battle with the wind isn’t over yet. We

have to secure the tents with large boulders and big logs to keep them on

the ground. Before turning in, we decide to get up at first light to avoid

more headwind.

The next day starts with the most beautiful morning

we’ve had on the trip. At 5 am, the river is like smooth, dark glass,

while the forest is a black outline, etched against the dawning sky. At

6:30 we launch into the still waters. The kids, wrapped in sleeping bags,

are sleeping in Kurt’s kayak. We paddle silently, savouring the serene

beauty around us. Within a few hours we come upon a camp on a gravel bar.

It’s the party with the inflatable canoes that had left Old Crow several

days before us. We call out and one man responds, “We’re just getting up,”

he says. “We’ve paddled all night to avoid the wind. We’re way behind

schedule....” Several hours later, in the afternoon, we encounter a motor

boat, heading upstream. The driver asks us if we had seen the party with

the inflatables. He has been sent for to pick them up and to ferry them to

Fort Yukon. This news spurs us on to complete the trip under our own

steam. Kurt reckons we’re only eight hours’ paddling away from Fort Yukon.

This evening is one of the warmest we’ve experienced. Sitting in my

Thermarest chair, watching the river in the golden sun light, I imagine

being on a tropical beach. Inside the tent, it’s so warm I have to strip

to my T-shirt. But by 9:30 pm the sun slips behind the forest and it gets

cooler.

Another perfect morning follows. Has Indian Summer

finally arrived? No. Our hope turns to disappointment when, after sunrise,

black clouds come sailing out of the East. Soon, we’re back to cloudy

skies, and cool temperatures. So close to journey’s end, my body is

yearning for a rest. I feel sluggish and tired, and my back is aching.

Paddling becomes a chore. Our lunch break stretches into two hours. Karin

and I don’t want to leave the warming fire. Before climbing back into the

cockpit, I down two Ibuprofen tablets with some water. They do the trick.

The aches and pains are switched off, and we paddle on. Our last camp is

on an island about an hour away from Fort Yukon.

|

Moments to savour: a

nice morning on the Porcupine River.

|

Early morning paddle before the headwind starts.

|

Tough voyageurs: Tarim and Teja

|

|

|

On a misty morning, we paddle past Homebrew Island, scanning the

opposite shore for some clearings. We want to avoid getting into the

Yukon River, because we would have to paddle upstream to get to Fort

Yukon, an almost impossible task because of the strong current. “I

think that’s it!” Kurt shouts, and points towards a blue tarp in the

trees. We paddle hard to escape the main current and pull into quieter

water behind several fallen trees. It’s not an enticing spot to end

our river journey. We have to unload the boats and haul them up the

steep mud bank. Under the tarp, beside a large picnic table, we start

disassembling the boats. It takes hours to get them and all our dirty

gear packed up. A trail leads from the picnic site towards the

direction of Fort Yukon. By noon we start carrying gear down the

trail, which ends, after about 1.5 km, at the northern end of the Fort

Yukon air strip. We have to make the trip several times, and it’s back

breaking work, especially since some of the boat bags are over 60

pounds. By 2 pm, we’ve hauled all the gear onto a bank overlooking the

air strip. Shouldering our day packs, and leaving our gear behind, we

start off towards civilization. |

|

End of journey: hauling the boats up the

embankment. |

Once we’ve crossed the air strip, we find

a gravel road and follow it. Several pick up trucks pass us. We keep

walking. Where is the town? I feel as if we’ve arrived from outer space,

and are now trying to make contact with humans. Finally, after about an

hour’s walk, we get to a building. A man is working under the open hood of

a car. Kurt inquires about flights to Fairbanks, and the man directs us to

the office of Warbelows Air. With the help of a van driver, we retrieve

our gear. Then we walk the streets of Fort Yukon, until it’s time for our

flight south to Fairbanks. From my window seat, I bid farewell to the

wide, brown Porcupine, the endless bush and the numerous lakes glimmering

in the evening light.

In Fairbanks, civilization greets us with a soft

motel bed, hot showers, and a Laundromat, but our experience with US

Customs and Immigration isn’t as welcoming. Kurt calls them in the

morning. “You have to come right away,” is their reply. The shuttle van

from the motel delivers us to the airport. One of the customs officers is

furious. “Well, folks, you can’t just enter a country illegally through

the bush, without first making arrangements,” he counters. We tell him

that we followed the instructions in our guide book, which mentions that,

after crossing the border, one should report to customs at the first port

of call. Since Fort Yukon doesn’t have a customs office, we decided to

report in Fairbanks. “The guide book could have been written by a

terrorist!” the officer snaps. We’re flabbergasted. Luckily, his colleague

is more relaxed. He hands us the customs forms. “Just fill them out, and

I’ll stamp them for you,” he says. After that, we’re officially in Alaska.

In the evening, we celebrate the end of the trip in the rustic Pumphouse

Restaurant. For the last time, we look at the maps and are amazed that we

traveled over 800 km under muscle power.

|